In conjunction with the Nashville Public Library’s city-wide celebration of beloved author Mark Twain, the Frist Center for the Visual Arts organized Thomas Hart Benton in Story and Song, presented from Oct. 2, 2009 through Jan. 31, 2010. The exhibition features more than 80 works, including 20 drawings from each of the three illustration projects he completed to accompany Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Life on the Mississippi. The exhibition also featured prints, drawings, and paintings relating to Benton’s deep love of American vernacular music.

- Thomas Hart Benton. Illustration for Life on the Mississippi, “If the fire would give him time to reach a sandbar,” 1944. Drawing and watercolors, 7 x 4 3/8 in. The State Historical Society of Missouri. © Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee /Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

The exhibition will be presented alongside Georgia O’Keeffe and Her Times: American Modernism from the Lane Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, comprising more than 50 works exploring the development of American Modernism through the eyes of a passionate collector.

“We thought these two exhibitions worked well together,” says Frist Center Chief Curator Mark Scala, “as they both look at America from different perspectives at a time when the country was moving from a rural, agricultural-based economy to one that was more urban and industrial.”

“By creating images that capture what he saw as the simplicity and dignity of everyday life in rural America, Benton strove to pay homage to his country’s people, history, and land,” says Katie Delmez, Curator. “While music was a tremendously significant part of his life and inspiration for his work, it’s surprising that, until now, the influence that music had on his work has not yet been fully explored.”

The Ballad of the Jealous Lover of Lone Green Valley by Thomas Hart Benton

The exhibition is divided into two sections. The first, “Thomas Hart Benton in Story” includes his delightful and lively illustrations of three of the most beloved works by Mark Twain, Benton’s favorite novelist. Like Twain, a fellow Missourian, Benton made his images with a raw, unvarnished tone, intending to present the quintessentially straightforward and unpretentious character of America. Although the two men were separated by a generation, their respective bodies of work were informed by their small-town, Midwestern upbringings.

The second section, “Thomas Hart Benton in Song,” includes works relating to his deep love of music. In addition to his talents as an artist, Benton was also a largely self-taught musician. Growing up, he listened to country music and was familiar with its artists and songs. As an adult, he began to play the harmonica and achieved enough proficiency to record an album (Saturday Night at Tom Benton’s, Decca 1931).

Benton often incorporated musicians and country ballads into his images. Several of the works in this section relate to specific songs, including

Wreck of the Ole’ ’97,

a ballad recounting the 1893 fatal crash of a Southern Railway train.

Others, such as

The Music Lesson,

show the pleasure of sharing music among family and friends, as the artist so often did himself.

Wreck of the Ole’ ’97,

a ballad recounting the 1893 fatal crash of a Southern Railway train.

Others, such as

The Music Lesson,

show the pleasure of sharing music among family and friends, as the artist so often did himself.

In 1975, the Country Music Foundation approached Benton to create a work based on the roots of country music. He began the project, The Sources of Country Music (on view at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum), in December of that year. In 1975, as he was putting the finishing touches on the work in his studio, Benton suffered a massive heart attack and died in front of the mural. During the years of development of the work, he submitted dozens of sketches to the foundation board for their comment and review, and ten of these works will be included in this exhibition.

Benton, who was born in Missouri in 1889 and died in 1975, is well known for his distinctive style and colorful palette. He enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago in 1907 and later studied in Paris, where he met Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, who undoubtedly influenced Benton’s style and choice of subject matter. In his early years as an artist, he traveled from the art scene in Paris, to New York, to the rural South, and home to Missouri. In his travels, he became a keen observer of America’s working classes and also became aware of the distinction between urban and rural cultures that is often reflected in his work.

From a review by Anam Cara:

Thomas Hart Benton in Story and Song features drawings and watercolors the artist created for three books by Mark Twain, as well as paintings inspired by American Folk Music. Benton was a part of the Regionalist movement that saw beauty in the ordinary men and women who populate ordinary towns and do ordinary things.

The exhibition highlights Benton's versatility. Each of the books was illustrated in a slightly different medium. For The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the artist used pen and ink to create clean, sharp, black and white images that snap with the same vitality the rascally Tom was known for. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, however, received a sepia wash "to evoke the muddy Mississippi River and the somber undertones of the book". Finally, Twain's memoir, Life on the Mississippi, is rendered in eloquently subdued watercolors.

The exhibition highlights Benton's versatility. Each of the books was illustrated in a slightly different medium. For The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the artist used pen and ink to create clean, sharp, black and white images that snap with the same vitality the rascally Tom was known for. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, however, received a sepia wash "to evoke the muddy Mississippi River and the somber undertones of the book". Finally, Twain's memoir, Life on the Mississippi, is rendered in eloquently subdued watercolors.

From a review by Anam Cara:

Thomas Hart Benton in Story and Song features drawings and watercolors the artist created for three books by Mark Twain, as well as paintings inspired by American Folk Music. Benton was a part of the Regionalist movement that saw beauty in the ordinary men and women who populate ordinary towns and do ordinary things.

One of the most intriguing elements of this exhibit for me is a serious of studies for Thomas Hart Benton's last work; a large scale painting commissioned by the Country Music Hall of Fame here in Nashville, called "The Sources of Country Music" (above). Sketches of individual characters followed by composition studies reveal the mind of the artist as he worked and reworked; positioned and repositioned. Fascinating!

Related Work:

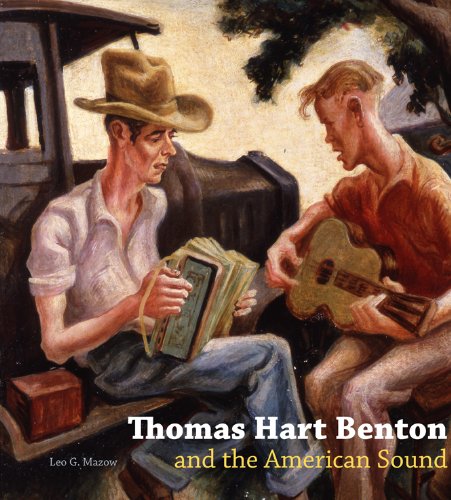

Alternately praised as “an American original” and lampooned as an arbiter of kitsch, the regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton has been the subject of myriad monographs and journal articles, remaining almost as controversial today as he was in his own time. Missing from this literature, however, is an understanding of the profound ways in which sound figures in the artist’s enterprises. Prolonged attention to the sonic realm yields rich insights into long-established narratives, corroborating some but challenging and complicating at least as many. A self-taught and frequently performing musician who invented a harmonica tablature notation system, Benton was also a collector, cataloguer, transcriber, and distributor of popular music.

In Thomas Hart Benton and the American Sound, Leo Mazow shows that the artist’s musical imagery was part of a larger belief in the capacity of sound to register and convey meaning. In Benton’s pictorial universe, it is through sound that stories are told, opinions are voiced, experiences are preserved, and history is recorded.